I shacked up with a Minimalist architect 25 years ago. We’re still debating every aesthetic decision on a daily basis, and what we live with is an extended dialogue between our definitions of beauty. The shapes and hues and patterns and materials and meanings are words. Their adjacencies form phrases and sentences. Every room is a paragraph. The house is a book, a history, a biography, a journal. And we rewrite it every day as we share this space, use things, collect more, rearrange.

Sometimes objects disappear. The kid might abscond with a little sculpture to her room. Or we give a bowl away to a friend whose domestic dialogue seems better suited to it. Or we break a vase – which is sometimes not enough to sever our attachment, which means there are little bags and boxes of shards and shreds cached away in drawers and closets throughout the house. More often these things we let into our lives are with us indefinitely, part of the unspoken language of two (well, three now) intertwined lives.

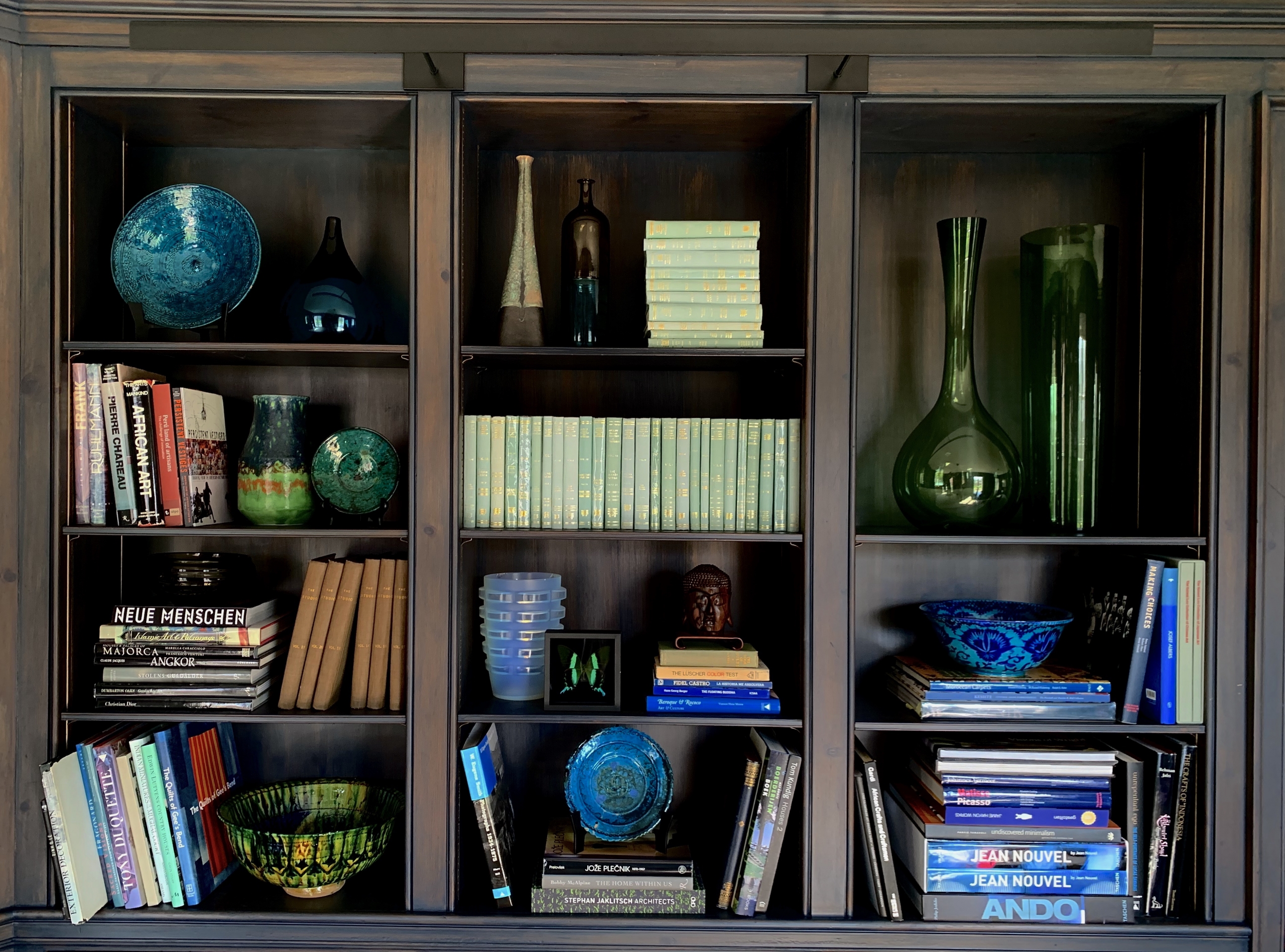

The very-not-Minimalist photograph I’m sharing with you is of one small corner of our dining room, which was designed over 80 years ago as a sort of sunroom – never mind that there’s precious little sun in Pittsburgh. Its next life was as the head of the household’s study, which is when the 1950 knotty pine paneling enters. There must have been prodigious amounts of smoking here, because by the time we came along the woodwork was a nicotine-induced shade of pumpkin. My partner glazed the entire room with an oil-based concoction of slate blue pigment…and developed pneumonia from the fumes.

Once the glaze (and the pneumonia) had cured, the shelves were full in an instant, starting with books. We’ve hardly met a book that didn’t have something to show us. Yes, they’re always looking for a home, but we didn’t let them take over entirely.

A huge bowl from Uzbekistan anchors one shelf. I have visited the Narzullaev family ceramic workshop a few times, but the time we went there together was the best: the Minimalist fell in love with the dripping glazes of Gijduvon, reminiscent in color and slipperiness of Tang Dynasty glazes – here applied over incised patterns that descend from the country’s Mongol period. The Narzullaevs have been part of the IFAM family since nearly the beginning.

On the opposite side of the shelves is a bright turquoise bowl from the Usmanov workshop in Rishtan, Uzbekistan. The ceramic tradition is different in Rishtan, arguably more influenced by Chinese export ware, as seen through a filter of Islamic patterns and the town’s history of mass production of dinnerware in the Soviet era. The sheen of the Usmanov’s glazes is due in part to the unique mineral signature of the buckthorn plant, whose ashes are part of the glaze recipe. Like the Narzullaevs, the Usmanovs have been with IFAM for a very long time.

In between, you see three blue-green plates from the potters of Istalif, Afghanistan. They consider their intense and gorgeous turquoise color palette as a secret belonging to their ancient cultural patrimony. Their artistic cousins across the border in Uzbekistan know how to make versions of this color, but not quite like this. The potters of Istalif came to IFAM once or twice since 2007, thanks in part to longtime IFAM stalwarts Sylvia and Ira Seret.

These IFAM-related objects, much cherished by us, are talking back and forth with all the other objects sharing the space. The blue and green jar by the great mid-century Italian ceramist Bruno Gambone is asking the Istalif plate next to it for the recipe for its intense color. No answer will be given. There’s a little envy going on. More harmoniously, the incised patterns of the Gijduvon bowl and the Istalif plate on the bottom shelf hum along to same old song: the lyrics don’t match but the melody does.

You can barely see it in the image, but the vase in the upper left chamber captures the intellect and soul of these constant exchanges. Designed by Vittorio Zucchetto and made in Murano in 1957, It starts off black at the top, and swells into intense aquamarine at the bottom. Inside, an exaggerated punt of black rises from the bottom, like a thought emerging and expanding from the deepest region of the mind – like a work of art rising up in its creator.

The dark wooden Buddha head I bought from a street artist in Bali 30 years ago also says something about this moment of inception. Just behind its beautifully rendered face, the dramatic grain of the wood speaks of the creativity, the invention that are always at work, making tranquility possible. The mind and the soul are constantly in play, regardless of what’s on the surface. The grain continues its undulations all the way to the heart of this sculpture, which seems to beat with a pulse when I hold it in my hands. It is alive.

There is more to say…about the glass and the moments in craft history they capture with equal parts force and fragility. About the books. About the people who made and sold these things to us, and where we met them. About the time of day and the sunlight and the wind blowing exactly at the moment we found them…because, believe it or not, we remember it all. We don’t just live with this art, it lives with us. Within us.

****

Keith is Editor in Chief and co-owner of Table Magazine, which chronicles the world food and drink scene as well as authentic and personal facets of design, travel, fashion and farming. He is president and co-founder of HAND/EYE Fund (2010 – present), which publishes handeyemagazine.com. HAND/EYE Fund’s 2010 “Million Hearts for Haiti” booth at the International Folk Art Market | Santa Fe raised many thousands of dollars to assist Haitian artisans, and went on to invest over $250,000 in helping the Haitian artisan sector recover and grow. He was the Executive Director of Aid to Artisans (2000-02), where he supervised operations of the $4.5 million international nonprofit agency, which grew to $8 million. He also served on the Aid to Artisans Board of Directors for many years. He currently consults in trend and color forecasting for Pantone and has a highly specialized color and branding consultancy called Chromosapien. His background is in the design industry, where he has been VP of Home Furnishings at Bloomingdale’s Direct, VP/General Merchandise Manager at Gump’s by Mail, and the Director of home furnishings at Saks Fifth Avenue, amongst other endeavors. His book, The Twentieth Century in Color (Chronicle Books, 2012) was published in eight languages. His most recent book, True Colors: World Masters of Natural Dyes and Pigments (Thrums Books, 2019) will be re-issued in a second edition in 2020. Keith’s graduate study was in American literature at the University of Michigan, and he holds a B.S. cum laude from Carnegie-Mellon University. Keith is a collector of global textiles and contemporary art, has traveled extensively in many of the home countries of Market artists, and is conversant in Italian and French.